I have been told my whole life, from many people, that it is what is is. In some instances it’s a funny platitude, and for others it becomes increasingly frustrating. It is what it is, but what if it wasn’t. At many times in our lives, its exactly that.

Almost a year ago, I headed out on a 1000 plus mile motorcycle ride up and down the High Sierras of California. I had never seen this part of the state and viewing it on a motorcycle is a true religious experience. The smells, wind and every changing natural landscape. It’s one of my favorite ways to move around the world.

I took this trip as a way to plan for the year ahead and clear my mind. Riding a motorcycle requires 100% concentration, no additional time to think about the stresses of life. Little did I know that this school year would be the last. Looking back, my intention for the school year was to focus on process over product and my personal goal was to try and stay more present in the day to day.

What follows is my journal entries from each night of the trip, accompanied with film photographs that I hand developed upon my return. Here’s to the journey.

Day1: 8/16/2024

This morning, I set off on a 1,200-mile, three-day trip across the Sierras. Even though I’ve lived in California for nearly 15 years, I’ve barely ventured beyond Los Angeles and San Francisco.

The drive up the 5 Freeway is not exactly inspiring. It’s the kind of trip where the destination is everything and the journey is an afterthought. This ride, though, is the opposite: a reminder that the journey is the point.

I planned the trip just three days ago, after unexpectedly getting a four-day weekend. Honestly, I almost didn’t go. But my wife insisted. “School is starting. We’re moving this summer. You should do it,” she said. She’s always right—wink wink.

So I went: 450 miles, all without touching the 5. I wanted to avoid interstates to see the actual state—because when we fly from metro to metro, we forget the in-between, the places that built this country.

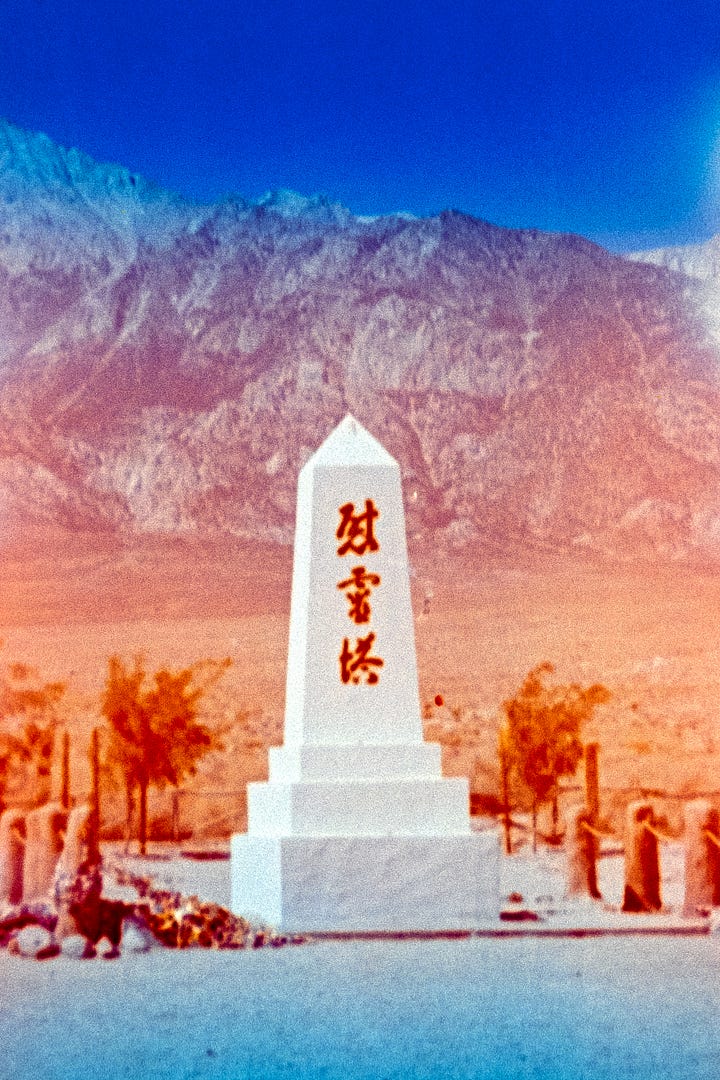

From Frazier Park to Maricopa to Kettleman City, Fresno, and beyond, the remnants of our past are still visible. In planning this trip I didn’t realize that Japanese internment camps were just two hours north of L.A., with Mount Whitney as a backdrop. I will visit this location on Sunday. Or the town of Chinese Camp—yes, that’s its real name—where Chinese railroad and mining laborers were once pushed to live.

Now, I’m writing this at the base of the Sierras, overlooking a creek, sipping a margarita. Life is strange.

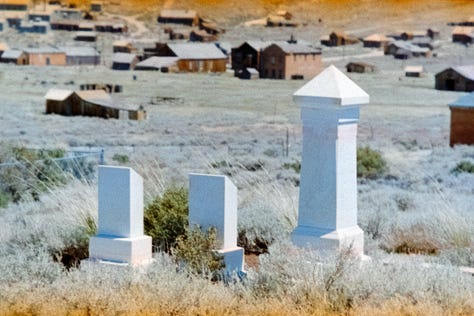

Tomorrow, I’ll cross into the Eastern Sierras along the north side of Yosemite. Small towns sit frozen in time—places built on choices and consequences. My destination is one of those consequences: Bodie

Bodie lost its final residents in the late 1950s. Once a booming mining town, the well dried up, the gold ran out, and people slowly left. I’m interested in capturing the contrast between towns built for prosperity and towns built from pain—all within 150 miles of each other. Why was one preserved and the other erased?

Day Two: 8/17/2024

I started early to reach Bodie by midday. Crossing the Sierras isn’t for the faint of heart—but it’s worth it. Seventy miles could take you over two and a half hours if you want to see anything along the way.

Along the way, you’ll see sections of the Pacific Crest Trail—a journey I’ll probably never do, but the idea still intrigues me. This along with natural mountain lakes and reservoirs allow for a detachment from our modern society. Descending from 9,000 feet, the small town Bridgeport reveals itself at the base of the mountains.

I stopped for a long lunch. The gray-haired woman behind the counter informs me this is the best burger in town. I had no way to verify that, but I hadn’t eaten any others—so I guess she was right.

This morning, I felt at peace. And then something shifted.

Trips like this give you much time to think. By the time I reached Bodie, my mind was racing.

If you're planning to visit Bodie, be warned: the last three miles are a rough washboard gravel road. I knew this going in, but still—my tail bag broke off the back of the bike. Thankfully, some kind soul found it and propped it up next to a stop sign. God Bless you, stranger.

As you crest the final hill, what’s left of Bodie reveals itself—redwood buildings, rusted-out cars, an old power plant and mine, and, ironically, a modern porta-potty for your convenience. They call this a “State of Arrested Decay”. From my understanding this basically means that the building are as they were when the residents left. Their will be no more upkeep, so they will stay like this until nature takes back over, which has already happened for some.

The wind whips at 8,300 feet. The sun feels hotter, even at 78 degrees.

Admission was eight bucks. A walking map cost three, but I only had enough cash for one. I chose admission and decided to wander on my own.

The church is one of the most intact buildings, though it leans noticeably. Inside another building, you can watch a documentary about the town.

Here’s what stuck with me:

Bodie found gold—but did he really find anything?

It’s safe to assume someone had already found it, had already lived there. But Bodie broke open the Earth to see what could be taken.

Resources.

Greed.

Consequences.

Bodie’s namesake died in a winter storm in 1859. The town that rose in his name became lawless—a gold rush paradise turned disaster zone. At its peak, the mines were raking in millions. But that was the rise before the fall.

The wind cut my trip short as the dust feels like needles. I make my way back out and head to my motel on Mono Lake. I arrived earlier than check in so I headed to the visitor center. Mono Lake is a remnant of my current home cities involvement in syphoning water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles. Be it from films like “Chinatown” or “The Longest Straw” the water from LA travels a long way and has a very controversial history. As you stand on the dry lake bed you can see how much water has been diverted to a desert hundreds of miles away. The more you know.

I finally check into my roadside motel, a window looks out onto the lake. I expect a great sunrise as I face due east. I unpack and head out for dinner in June Lake. I find a small taco truck nestled next to a brewery to do this part of the writing. It’s small and quaint, the burrito hits the spot. The air is cold in these mountains, even in August.

Day Three: 8/18/2024

I was right, the sunrise was spectacular. Today I will head south from Mono Lake to LA passing Mount Whitney and Manzanar. Hard to believe a bustling gold town was still functioning 150 miles from Americans being imprisoned in Manzanar. I decide to take a little more scenic route through Mammoth Lakes while the air is crisp. Although a big skiing town, Mammoth seems quiet during the summer. I sit at a cafe and people watch as most will probably be making the same journey as I am today. It’s always strange to know that most of the people you cross paths with, is just that. A crossing, nothing more. They are off to their journey.

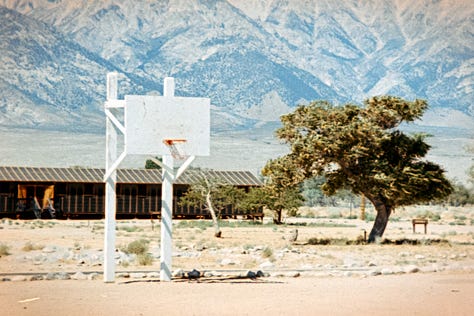

The air starts to get warmer as you come out of the high elevation. The land gets dry, probably from the diversion of water to LA County. I see the exit for Manzanar, but I don’t see all that many structures. I think about the arrested decay of Bodie, and the lack of visuals for Manzanar. Why is one curated and the other left alone?

From the highway you can see the gate and guard tower, along with the main meeting center that now houses a museum and gift shop and a few replicas of the barracks that were placed for those imprisoned. The rest of the buildings have been dismantled only their concreted foundations left to see the scale and scope.

You could walk around if you like, but it’s quite sprawling so I took the drive and stop method. Each new stopping point shows gardens and placards stating what would have been there. All the while you can see the beauty of Mt. Whitney in the background. A mammoth point that feels almost hopeful against the travesty of this place.

I make my way back to the start and take time to look at the photography books in the visitors center. I had seem photographs before and always wondered how they were taken. Toyo Miyatake, a professional photographer, built a camera from pieces he had brought with him. These images would be a window into how Miyatake saw the experience, an intimate account of how he saw the world.

Before making the final push back to LA I stopped to talk with the park ranger. I wanted to know why Bodie is left as is, and Manzanar is curated. The only answer I got is that Bodie is state ran and the latter, federally ran. I guess it is what is is.

But what if it wasn’t?

I’ve had this article in my drafts since I wrote it back in August of 2024. Thinking over the past few months, ideas of the past have come to the surface while we can still view the scars from the last time America tried them. A water diversion destroys communities, while “Relocation Camps” imprison American Citizens.

I think its easy to say “it is what it is” because it allows us to move throughout the world not thinking about our connectivity. What this ride taught me is we are more connected than we like to admit. The ride showed me the scars of our past, but also empowered me to share the stories that were left in plane site. Just because it’s always been done some way, doesn’t mean it’s the best way to do things. Keep searching and asking questions, there’s always more to learn.