I can still remember the feeling I felt when I finally acquired distribution for my first feature film “Autumn’s End: The Horror”, I was beyond excited. The years of work, the amount of no’s we were told, but somehow we still made it. Multiple distributors passed, despite enjoying the film. A few said they couldn’t figure out how to market it without a name talent. But despite all of that we finally got an offer: No money upfront, and a 50/50 split of all profits and they would cover marketing costs. As a reference, this is considered a good deal for an indy film.

Six years have passed since signing the contract and sharing our film with the world. At the height of the contract, we were in dozens of countries, in at least three languages, and streaming on over a dozen platforms. Looking back I remember thinking how wonderful this was going to be. We would be able to pay everyone back their deferred pay in no time. Little did I know that this six-year partnership would turn into a master’s class on what really happens during the distribution process.

The Reality

Distribution deals are what every filmmaker hopes for - sitting at home, thinking about your story and how others will view the film. What will they get from this story? How will they be able to watch this film? While most of us don’t start making films to get rich, we do understand that there is money to be made if we go through the process. We make the DCPs, pitch decks, and websites. We spend thousands of dollars on film festivals, even if they may not watch the film. We do these things, thinking selling our film will lead to the next step.

However, the deals are not in favor of the artist, and when you receive pennies for your work it hurts even more. I’d rather give my work away for free (which is what I do now).

Over the course of the 5-year contract, I received a total of $953.46, or $.52 per day, all of which has been given to the cast and crew. The largest payment came in Q1 of 2019 where we netted $152.58. This is the reality. Some distributors lock in your film for upwards of 15 years making the situation worse. You may be asking how it is possible for a film to be on 6 platforms and only generate $150 dollars in revenue for the artist.

At the time of the aforementioned quarterly report, Amazon was paying roughly $.04 per hour or roughly $.06 per 90-minute feature film1. With half going to a distributor/aggregator, you end up making $.03 per view of your 90-minute film. At these rates, an independent filmmaker would need over 3,000 hours of views to make the $100 payout threshold that Amazon has set before they write a check. This is the true financial landscape of a distributed indy filmmaker that finances their own films, following all of the rules that are placed in front of us to “succeed”.

As of the time of writing this article, I have acquired traditional digital distribution for two feature films, both of which have had similar outcomes in profit returns. In both cases, the communication has been low and I have never seen a view report of how many people have actually seen the films. The lack of transparency in view counts only adds to the confusion about how financial compensation is calculated.

My Final Payment

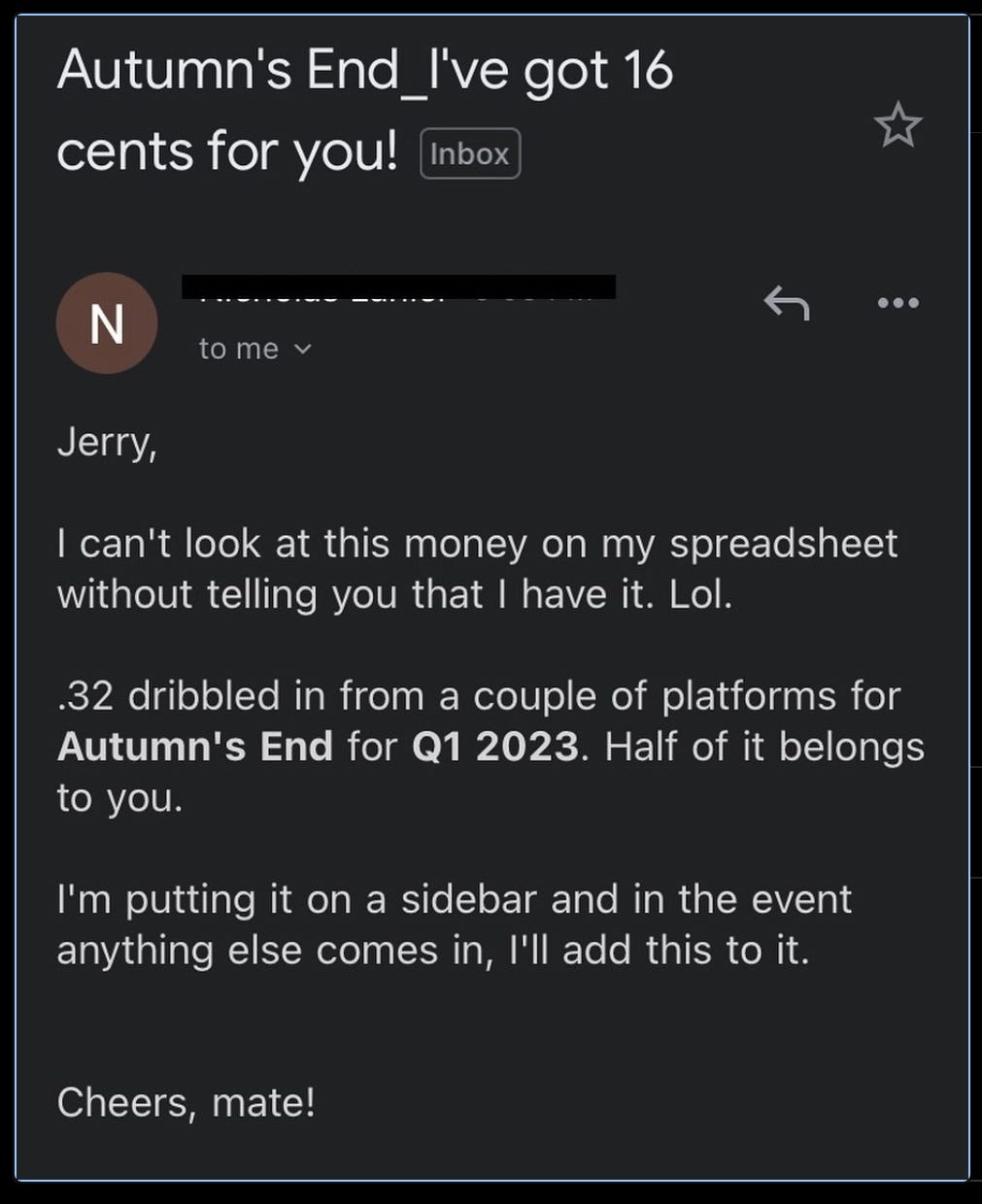

This past week I received an email from my distributor stating “I’ve got 16 cents for you!” There were a lot of feelings associated with reading this email, but the one that I felt the most was disappointment. A distributor, at least in my eyes, is a partnership. An artist makes a piece of work, the distributor helps get it seen and we split the profits. If I win, they win. I have made three feature films at this point, we could have worked together multiple times but instead, I got 16 cents.

The WGA/SAG strike, which I have written about previously (Click Here), has shown us that for the current industry to operate, people have to be taken advantage of. This has been even more clear with the resurgence of the show “Suits,” which has over 3 billion collectively watched minutes on streamers. The writers have only received $3000 in residuals2. We love our entertainment but at what expense?

What Can We Do?

In my opinion, a lot:

I believe we can start going local again, but what does that mean? It means supporting your local artists. This Substack has almost 600 free subscribers but my youtube that gives films away only has 190 subscribers. If you like what I am doing I urge you to subscribe to the Bronson Creative Youtube, it costs nothing and helps tremendously. Do you like what you are reading and think it would help others? Then share the Substack with them. Do you have something you think would be of interest to me? Please share it with me, I'm always looking for new artists.

Do you have an artist in the family, or maybe a friend that is aspiring? Ask how you can be a part of their journey. Maybe you could share their work with others, or host a screening of their film. What does a more community-based approach look like? If you are in a big city hub, you most likely have artists in the same situation I shared above.

Buy physical media/go to theatres and art events. Watching films as a community allows us to collectively engage in conversation. Streaming has led to a decline in physical media while allowing streamers to decide what we see and for how long. “The Horror” was originally on Amazon until they decided it wasn’t getting enough views and then it was removed. By owning physical media it allows us to share films with our community and watch whenever we decide, even if the internet goes out.

It’s Only a Movie…

I just finished up the first week at my new school where I will be designing the film and media program from scratch. Over the past four years of teaching, I have realized that education is the only way to end these cycles of prey. Learning to make a film is part of the process, but how we treat each other is more important.

“It’s Only a Movie” is a Hitchcock quote that I’ve always enjoyed. It means don’t take the film too seriously when you are making it, have some fun. Little did I know that the second half of the quote was “…, after all, we’re all grossly overpaid.” This changes the quote entirely and shows the disconnect between the way the industry is perceived and how it operates.

In starting this film/media program it is my goal to fill in the gaps and empower students to find their way through the history of the medium. In doing so, I also hope to fill in my blind spots as an artist. While it’s true that it’s only a movie, that movie has an opportunity to communicate on a global scale. That movie has the opportunity to change minds and inform others that there is someone like them experiencing a similar human experience. A movie also has the opportunity to show the world that some are grossly overpaid, but most are not.

It’s time to tell the other side of the story. It’s time for artists to speak up and share their experiences. While it has been like this for quite some time, it doesn’t have to stay that way. In doing so I would like to offer a rewriting of Hitchcocks words for the 21st century.

“It’s our movie, and we have been grossly underpaid.”

-Jerry J White III-

Do you have a similar story? Share it with me by leaving a comment.

https://digiday.com/future-of-tv/amazon-royalties-video-makers-uploading-prime-video/

https://nofilmschool.com/suits-residuals